Author: Rawan Abbas – Egyptian Researcher

The Vicious Cycle of Poor Education and Income Insecurity

At the beginning of the 2022 – 2023 academic year, 15 students were injured, and one died in a public school in Giza when a concrete stair wall collapsed. This incident is one of many examples demonstrating the poor quality of public education in Egypt. According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the illiteracy rate in Egypt was 25.8% in 2017, with a school net enrollment rate of 75%. Factors contributing to poor education quality include overcrowded classrooms ranging from 30 to 70 students, a mismatched and overly intense curriculum, insufficient teacher training, low salaries, and inadequate facilities and infrastructure.

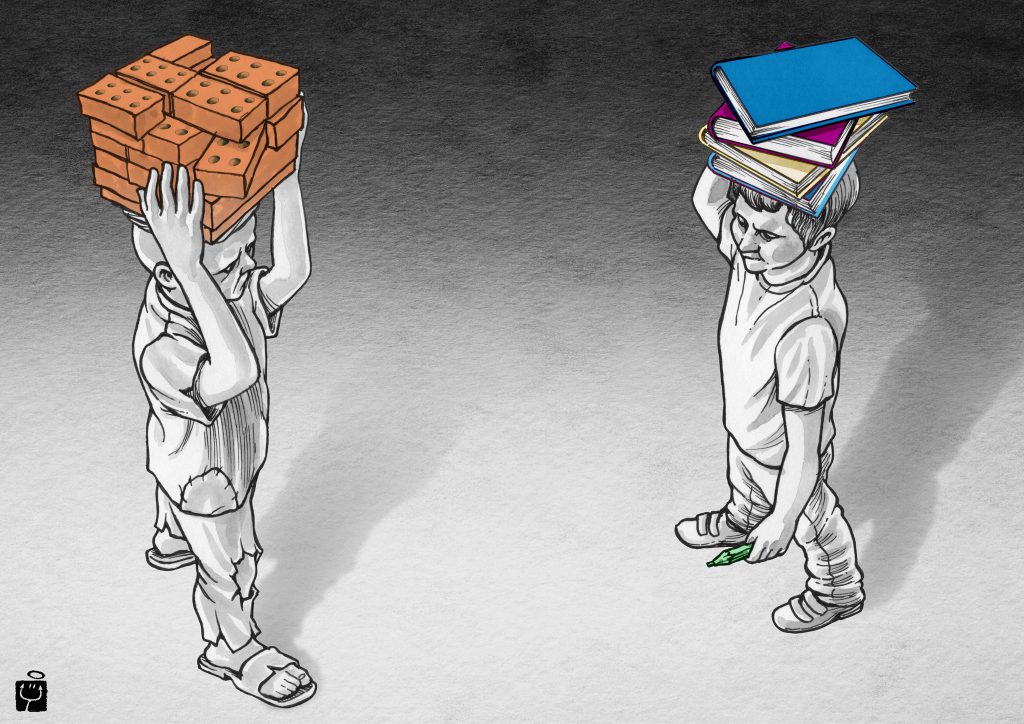

These factors do not only immediately affect students’ cognitive development, knowledge acquisition, and learning process, but also significantly impact their long-term employability. Poor education results in low-income job opportunities, perpetuating the vicious cycle of generational poverty. Therefore, it is crucial for the state to provide universally accessible and inclusive quality education. Effective education policy relies on three interconnected aspects: a social protection floor guaranteeing minimum income security, genuinely free or subsidized public education, and ensured quality of education. Although the Egyptian government claims to offer free or subsidized public education, it prompts critical questions: How is this “free or subsidized education” defined? And what genuine benefit does it offer when quality and inclusivity are compromised?

The concepts of minimum income security, subsidized education, and educational quality should integrate within a comprehensive social protection system, inclusive of basic income security, universal healthcare, and child support. Existing governmental social programs, such as Takaful and Karama and Foursa, operate within a neoliberal framework. These programs selectively define poverty, lack comprehensiveness, and fail to adapt to changing economic circumstances. Cash transfers alone neglect broader critical issues like education quality and healthcare affordability, thus are unable to break the poverty cycle.

Amira[1], a teacher earning 830 EGP monthly (26.8 USD in January 2023), faces substantial difficulties covering her child’s school expenses (700 EGP for language plus 300 EGP excluding books), yet she does not qualify for government programs. Such cases underline systemic inadequacies.

Underfunding, Privatization, and the Hidden Costs of “Free” Education

In early 2024, Egypt allocated only about 1.7% of GDP (around 5.3% of total government expenditure) to education—falling short of both its constitutional goal of 4% of GDP and the broader international benchmark of 4–6% of GDP / 15–20% of public spending. Underfunding has led to teachers working without social or medical insurance and receiving wages artificially adjusted to meet minimum wage standards. Manal[2], who is also a teacher, cites how her contract is merely ostensible, meaning that it does not incorporate social insurance and that salaries are fabricated to meet the national minimum wage. This type of income insecurity affects the quality of education that children in such households can afford, typically public education. Students enrolled in public schools pay a minimum of 305 EGP and a maximum of 520 EGP (for the academic year 2021-2022) depending on their grade; however, this tuition excludes book expenses, which must be purchased exclusively from government bookstores due to annual curriculum changes. Since public schools are underfunded, they rely heavily on financial support from students’ parents. For instance, Manal, who has two kids, one in primary 6 and the other in primary 5, mentioned that “all parents had to collectively participate in printing exam papers because their school did not have the finances to do so.”

With public education being inadequately equipped, families resort to alternative forms of education, notably private tutoring. According to CAPMAS, Egyptian households spend around 28.3% of their annual budget on private tutoring. The core issue is not private tutoring itself, nor will it be resolved through crackdowns on private tutoring centers or by bringing these centers under government supervision and subjecting them to Value Added Tax (VAT). Instead, the problem fundamentally lies in the poor quality of public education itself.

Private tutoring is neither the only indicator of poor public education quality nor the only form of cost-prohibitive education. More affluent households resort to private schools, as a more expensive but still inaccessible and exclusive alternative. A far more expensive and exclusive option is international schooling, where tuition can reach up to half a million EGP per year. These schools offer various curricula: American Diploma, IGCSE, IB, and francophone systems, with some more costly than others. In this context, the more families pay, the more they secure what is now defined as “quality” education. However, the definition of quality has expanded beyond knowledge acquisition; it now includes networking with powerful and influential social circles, as well as access to corporate-sponsored opportunities. This version of “quality” education ensures a high level of income security—but only for those who can afford it. For others, these opportunities remain out of reach.

Similar hierarchies exist in higher education, though they are even more convoluted. Most public university faculties are stratified into Arabic, English, and French sections, and further divided between mainstream and credit-hour systems. Tuition varies by language and system: English and French sections are more expensive than Arabic, and credit-hour systems cost more than mainstream. A more expensive option would be Egyptian private universities, and an even pricier one would be international private universities.

Who Gets Left Behind: Poverty, Rurality, and Disability

Conspicuously absent from both general and higher privatized education hierarchies are vulnerable groups. These include people in extreme poverty who cannot afford even private tutoring, those living in rural areas, and people with disabilities (PWD).

First, for households in extreme poverty, dropping out becomes a rational choice,even for students nominally covered by government social programs. A basic cost-benefit analysis, makes this clear. On the one hand, education is not genuinely free; without the financial means for private tutoring, students gain little from the process. In this case, the fatigue and time spent attending school outweigh any tangible benefit. On the other hand, dropping out to help with housework or to work increases the household’s income security. In such circumstances, leaving school becomes the most logical option. This reveals why cash transfers and entrepreneurial training schemes are insufficient for income security: they remain fragmented and disconnected from broader systemic needs.

Second, students in rural areas face forms of inaccessibility that urban students often do not. Marwa[3], who attended a public school in a small town in Lower Egypt, shared how difficult it was to continue her education in Cairo. She initially rented a shared apartment, but her parents could only support this for two years before it became a financial strain. To continue her studies, Marwa had to work full-time while attending university, an arrangement that negatively impacted her academic performance.

Third, people with disabilities face multiple and compounding barriers. According to the UNESCO, only 43% of PWD are enrolled in schools, a statistic that fails to reflect the full reality. Among those enrolled, many face inaccessible accommodations, non-inclusive curricula, and a limited range of options. Even private schools are not always better: Manal explains that the private school where she teaches charges 6,000 EGP annually and violates the 5% inclusion rule. Instead of integrating PWD, the school designates 95% of its space for students with disabilities to profit from the lack of options. Though the school has competent teaching staff, the classrooms are in poor condition, roofs leak when it rains, and the infrastructure remains generally non-inclusive. Still, “parents will pay anyway because no other school will accept their children.”

This poor and non-inclusive education system cannot be analyzed in isolation from government social programs; the two are deeply interconnected. While the Ministry of Social Solidarity offers monthly stipends, aid, pensions, tuition waivers, and scholarships to PWD, these benefits alone do not secure access to quality education or future employment. Without systemic change in educational quality and inclusion, income security for PWD remains out of reach.

Students also engage in informal upskilling, dedicating additional time beyond formal education to enhance employability. A 2009 and 2014 Population Council survey revealed only 12% acquired skills through formal education, aligning with the World Economic Forum’s 2021 projection that 40% of workers would require upskilling by 2024. Nouran[4], a business administration graduate, paid 10,000 EGP for marketing courses due to insufficient college training. Informal upskilling remains largely unregulated, complicating accurate assessments of formal education’s effectiveness.

Social Protection as the Path to Educational Equity

In light of all that has been explored, it becomes clear that the current model in Egypt is deeply inadequate for addressing the lived realities of educational inequality. Addressing these challenges requires reimagining social protection as a comprehensive system, not a patchwork of selective interventions. A truly inclusive system must guarantee not only free access to education but also its quality, and ensure that people are not left behind simply because they live outside Cairo, or because they are living in poverty, or living with a disability.

This vision of social protection must be rooted in a broader understanding of poverty, one that sees poverty as dynamic and interwoven with a range of structural inequalities, rather than a fixed income threshold. The lives of Amira, Manal, Marwa, and Nouran provide us with examples showing that existing definitions and tools are simply too narrow to grasp the complexity of what it means to survive and try to thrive in Egypt today. What is needed instead is an approach that draws from the actual conditions people face: their geographic locations, their household compositions, their access to informal skills, and their experiences navigating state and private education systems.

Achieving this kind of responsiveness will require better data, more grounded analysis, and ultimately, more political will to challenge the logic of austerity. Funding must be rethought, through transparent, progressive taxation that holds elite educational institutions to account, rather than placing the burden on already struggling families. Without such changes, the state will continue to reproduce the same cycles of exclusion it claims to be addressing.

[1] Examples presented in this article are drawn from interviews conducted by the author. Interviewees’ identities have been anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

[2] Examples presented in this article are drawn from interviews conducted by the author. Interviewees’ identities have been anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

[3] Examples presented in this article are drawn from interviews conducted by the author. Interviewees’ identities have been anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

[4] Examples presented in this article are drawn from interviews conducted by the author. Interviewees’ identities have been anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.